Modern inertia affects each of us differently. Some of us run about their daily errands with unusual, religious commitment to fend it off, others try to procure peace and contentment through recreation or whatever, to keep those nerves at bay. The alarum went beyond just paranoia or personal traits: it betrays something profound about our epoch. Disconcerted, we are looking for symbols to make our lives bearable. We turn to different art forms for a tip-off, to no avail. Then, we become listless, world-weary (Weltschmerz). ‘What could be done about it? What could remedy our frantic today-ness?’

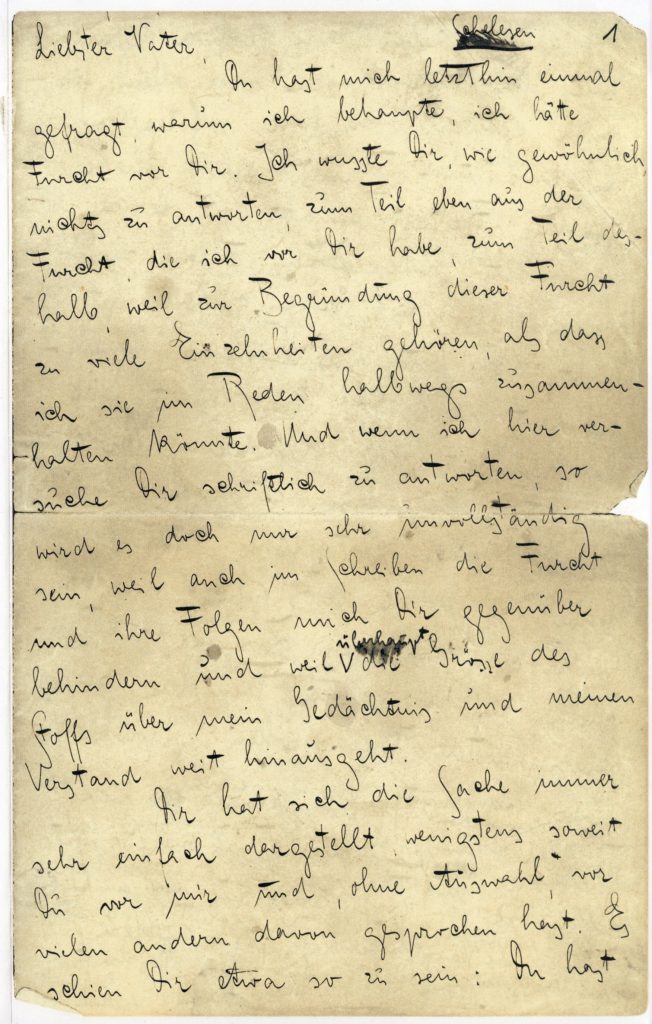

Franz Kafka (1883 – 1924) too wasn’t quite flattered by the course the world has taken. His literary output is generous: three novels, about forty-five short stories, numerous essays, letters (including the deeply personal ‘Letter to a Father’), and notebooks. Liable to neurotic bouts, however, Kafka implored that they be burned before he passed. Contrary to popular belief though, Kafka did not ask to burn all of his works, only the unfinished ones. But Max Brod, his lifelong companion and confidante, thought otherwise. As a matter of fact, Brod defied the will in full measure, to which we owe him much, for even his unfinished works show a striking clarity and greatly enrich the literary canon. They showed that he was deeply concerned with the individual, hemmed in by the facticity that shaped their life. Yet, instead of focusing on propounding heroism, Kafka wanted to navigate the diminished human spirit. Let’s think about it in greater detail.

Kafka’s central character is usually a downtrodden, cowed individual who is forced to watch the city mures rise and the sharp turns of alleys grow subtly surveillant and, wringing his hands, realize full well that nothing could be done about it. He is outspaced in a world that clamantly tries to possess him. In this sense, Kafka’s creative work served as a display of his personal frights, only in a covert, to-himself manner. But Kafka has never explicitly stated his obstreperous relationship with the world. He never aimed at one sphere of life. His world–or worlds, for that matter–were absurd, yes, and eerie, but there is little merit in searching for the political or the sociological there. Nor are his characters strong-willed dissidents or Sisyphean figures; really, many of them are portrayed as compliant and weak-willed. It’s much more likely that they fall victim to the meagrest agitation. And this is exactly what Kafka wanted to explore. He navigated through human incapacity to find what one can do when one is incapable, or, to intensify this dialectic, what one can do when one cannot do anything. And neither in a political or sociological or technological or whatever sense. His aim was existential; it is about all of us.

To amplify this, there is a particular hue Franz painted bureaucracy and authority in. Government officials play little role; the System or Authority is what matters and what always remains a faceless creature with unknowable designs. Its nature is twofold: it embodies, as it were, itself, and the whole world. In turn, the K’s—the main characters—are more than compagnons de misère; they represent the whole human race, and how it rushes about life, whether in macabre fashion as in “The Trial” or in an automaton-like one as in “The Castle”. For narrative purposes, the circumstances are elevated to the fantastic yet the idea itself stayed uncannily universal. The motives of the System are forever undeducible and genuinely strange. What’s more, its hostility occurs in due course; from this stems the isolation, the alienation of modern man. One must brace oneself in this absurdity and indifference which are far from surreal; they are, in fact, congenital to the human condition. Taken individually, each of us is K in his story, a story of ethical struggle against technology, of subsequent estrangement and hostility borne out of incertitude. In this sense, Kafka’s work seems almost prophetic.

At the meeting point, the two parts show us the tension that was so important to Kafka. It is forever the conflict between the Man and what institutionalises him. He acknowledged the fact that one cannot wage war with phantoms. In ‘The Trial’ there is an episode where the priest tells K a story. It is about a man who eagerly tries to get in the law that is behind a door. The doorkeeper, however, stops him, saying that cannot be admitted now but soon. The man waits years. Then some more years. Right before he dies, the man asks the doorkeeper how come no one has tried to get in. The doorkeeper says that the door was meant only for him; he should close it now.

The Man was never meant to be admitted inside the law, or the System. Yet it is clear, if we consider all of the above, that what Kafka was trying to do is a kind of negative heroism, in his bugs, courtrooms, and castles. The impossibility of us being admitted is by no means the reason for inaction. Because that would lead to drifting towards what’s anyhow inevitable. Yet it is because we are forever stirred that we must bear it responsibly. Kafka’s characters were all such prominent sparks because they tried. Yes, all of Kafka’s characters ultimately fail. But there is, I believe, a difference between us and his characters, for they also thought that one could enter the System, be a part of it, as it were, complement it. I urge us not to think that way. He urged us not to think that way.

The term ‘Kafkaesque’ was coined somewhere in the 1930s, between the frail echo of the First World War and the adumbration of the Second one, and the word has been resonant ever since. For a century, his outlandish stories and personal outpourings aided people with finding the meaning in life’s journey. As Prof. Oliver Jahraus said in an interview: ‘Kafka transcends the time in which he wrote, identifying problematic issues of the modern age that, regardless of all debates about postmodernism and post-postmodernism, remain relevant today.’ Indeed, there’s truth to that.

Written by Radomyr Lesnykov

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons (CC0))