Body, Mind and Madness – Exploring the Inside of Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers

In his work, David Cronenberg looks into the dark corners of the human mind, breaks taboos, strips human beings of their moral spine, and shows viewers the sick reality of the world. While watching, the transition from repulsion to fascination is a very short route – his films carry something that doesn’t allow the viewer to look away, and Dead Ringers is one of them. As Cronenberg himself said, I’ve had a response to the movie that I’ve never gotten from any of the other film.[1] Cronenberg skillfully interweaves in this tragic story identical-twins motifs such as eroticism, narcissism, dehumanization, and mutations of the human body, along with individualism or lack thereof. Everything in Dead Ringers boils down to transformation, both of body and mind. After watching it, a deep emptiness and sadness are left in the viewer, because one can tell that this is what the film is about – the unimaginable sadness of mankind and its life. The director himself revealed:

I went to one of the first public screenings in Toronto and one guy, a doctor, said, ‘Can you tell me why I feel so fucking sad having seen this film?’ I said, ‘It’s a sad movie.’ Then I heard from someone else that a friend of his saw it and cried for three hours afterwards. So I thought, ‘That’s what it is. That’s what I wanted to get at.’ [2]

As William Beard notes in The Artist as Monster – The Cinema of David Cronenberg, the subject of analysis in the film were volatile and fractious gynecologists, Beverly and Elliot Mantle, identical twins living in utter symbiosis. Brothers, who depend on each other and simultaneously need each other, have a relationship that is uneasy for them, but to end it is even more difficult. The subject is torn between openness and closedness, development and stagnation. They have lost their individual identities, although one could make the claim that they never had one. Cronenberg breaks down the image of the archetypal male, who in Dead Ringers faces the anxiety of separation and the obstruction of the boundaries of both reality and relationships. The director returns to the theme of being entangled in an ambiguous relationship with another man and plagued by nagging questions about his own identity. In one scene, it is said that no one can separate the twins, and they are seen as one man. Mantles are one living organism, in which whenever one organ stops functioning properly, the others are affected. The progressive degradation and dehumanization of dependent people manifest themselves in the film through the use of drugs and medication, the loss of control over reality. Beverly, in the course of his relationship with Claire, admits that they have always shared everything – their identities, experiences, and people – but after he met her it began to bother him. The frame below depicts one of Beverly’s nightmares, in which the brothers’ bodies are joined by their abdomens. It appears in the film as a recurring reference to the Bunker brothers – Chang and Eng – from whom the term Siamese twins was coined. The Bunker Twins and a clear reference to them will also be discussed later in the essay. Beverly and Elliot, despite the lack of physical connection between their bodies, were entwined with each other in mind and soul. The dream reflects his psychological state and portrays the brothers’ complex identity. The meaning of this dream can be interpreted ambiguously – one solution is the desire to escape and clearly separate to start his own life. Claire bites through the fold of skin that connects the twins – it represents their separation and release, the creation of two separate entities independent of each other, and the woman who tries to save them from ultimate perdition. In contrast, one might think that it is the very opposite – a desperate desire to connect even more deeply with his brother in fear of separation. Beverly is an introvert who lives in his brother’s shadow – it is Elliot who attends public events and gives speeches about their research (which Beverly does alone, away from the public). Bev’s relationship with women is also complicated – he functions mainly on the doctor-patient surface. Elliot, an extroverted, elegant, and gallant man, attracts women, which he then passes on to his brother so that he does not have to step outside his comfort zone and abilities. He also says during one scene that if it weren’t for him, his brother would have gone on without experiencing the sensation of sexual intercourse. Bev doesn’t tell Claire to separate the twins, he only expresses his confusion and embarrassment and doesn’t want any sexual relations while his brother is watching. So is it a desire to separate or a paranoid fear of abandoning and starting an independent life that he doesn’t know?

In her book Phallic Panic: Film, Horror and the Primal Uncanny, Barbara Creed states that there are films appearing in cinematography that are an interesting examination of male hysteria, which is a symptom of the failure of its male protagonists to create life.[3] In Dead Ringers, the brothers run a clinic to help cure female infertility, thus contributing to the miracle – new life. Cronenberg presents the hysterical nature of a man who is unable to control a woman’s reproductive system. Usually emotionality and hysterical behavior are attributed to the woman. As Creed presents, Showalter lists these as “fits, fainting, vomiting, choking, sobbing, laughing, paralysis.”[4] One can conclude that female infertility is an abnormality, a malfunction of the body according to its biological, textbook definition, which slowly drives the brothers to madness. When Beverly and Elliot meet their new patient, Claire, they discover three cervixes in her body. Through their love of medicine from a very young age, the brothers take turns marveling at their discovery. There is also a dialogue between Elliot, who pretends to be Beverly, and Claire regarding the literal interior beauty of humans and the idea of beauty contests in which internal organs would be judged. This is the first of the foreshadowings of the revulsion and fascination that subsequently appear, which seamlessly intertwine with each other and even function simultaneously.

In one scene, Claire mocks Beverly’s name, saying outright that it sounds like a female name. She is faced with a very rapid and aggressive response from the man, which she then concludes with the words:

Listen doctor. I think there’s something wrong with you. I don’t know what it is. I can’t put a label on it but you’re subtly…I don’t know…schizophrenic or something.[5]

The brothers, who seemingly live normal lives, share their lives, and their identities are fluid by swapping them, it is difficult to recognize who is who, which can also be exhausting for them to play the other person. Beverly is not exactly schizophrenic, but the play between the brothers can create that illusion. Twinship can be described as a pathological state from the start.[6] Others, however, identify the brothers as a single personality with schizoid features of contradiction.[7] An article in American Imago, Dead Ringers: A Case of Psychosis in Twins, provides a different perspective on Beverly and Elliot’s condition. The author notes that to understand the twins’ mutual destruction and insanity, it is necessary to focus on psychoanalytical and psychopathological approaches. She disagrees with Creed’s interpretation of male hysteria and concludes that the phenomenon taking place is most probably psychosis. In her argument, Oster refers to Freudian philosophy, which states that neurosis is the result of a conflict between the ego and its id, whereas psychosis is the analogous outcome of a similar disturbance in the relations between the ego and the external world.[8] (1924, 149) Based on Creed’s and Oster’s statements, one can conclude that men’s experiences are not hysteria because, as Oster says, hysteria is mostly harmless and does not cause sexual obsessions, unlike the brothers’ behavior. Creed, on the other hand, mentions symbolic castration – the separation of an infant from the mother’s womb, where it would so desperately want to stay. As mentioned earlier, after meeting Claire, the lives of both brothers begin to shatter. Can it be said, then, that the woman is the subject who brought them into this world and later led to its downfall? The entity they desire and hate?

The perception of women in Dead Ringers gradually deteriorates as Beverly’s mental state becomes worse. Initially, the human body was the brothers’ main fascination – especially the female body and its insides, because, as one might assume, this is why they run a gynecological clinic together. By doing so, they can avoid ‘male hysteria’ by having control over female insemination, without the physical act. Cronenberg pushes women towards body mutations and abnormalities in his films. The image of the female body in Dead Ringers is distorted, mutated – providing space for reflection on the very essence of the body, its limits and possibilities, and the relationship between identity and the corporeal. These portraits show that the power of sexuality (and the body in general) to dissolve categories and threaten ego-subjectivity is a power very much to be feared.[9] As seen in Dead Ringers, sexuality and

human desires can cause the human body to defy the mind and slowly move toward self-destruction. A doctor with an intellectual and rational mind, trying to rely on facts and medicine, exposes himself to the danger of female monstrosity. Thus Claire Niveau is a complete deviation from the norm, a fabulous monster, who is both familiar yet unfamiliar. She is a woman whose potential fecundity is both fantastic and terrifying.[10]

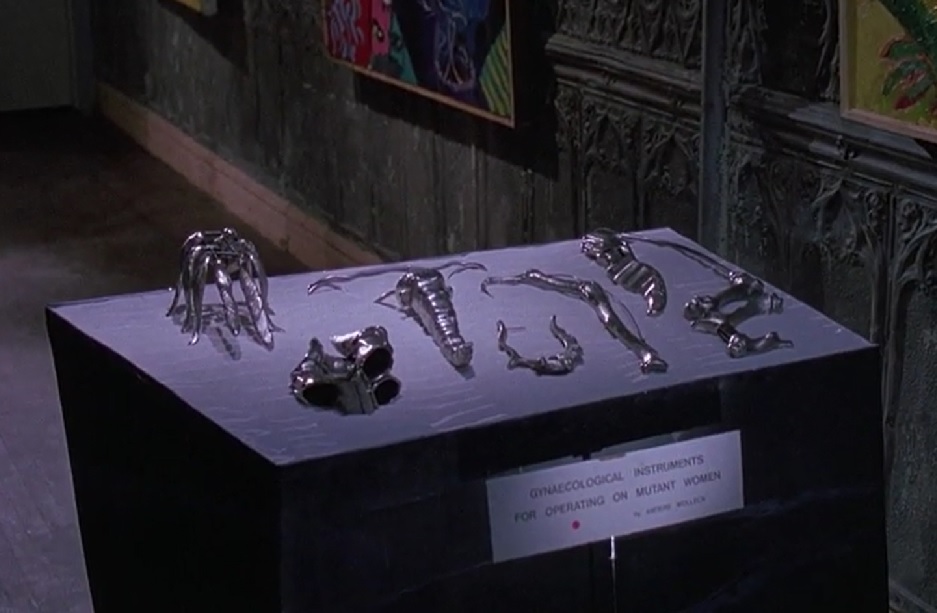

Claire becomes a barrier between the brothers. She has three cervixes, the illusion of a triangle, the exact number of people who are entangled in this difficult relationship.[11] This unusual affliction and the relationship with the woman slowly drive Beverly insane, especially after Claire’s alleged cheating. He becomes a character who is unable to accept the imperfection inherent in human nature. His obsession with mutated women commands him to frantically develop medical instruments to cure women of their abnormal dysfunctions. While studying medicine, the Mantle brothers create their proprietary retractor and use it during one of their lectures, where they perform mock surgery. Their supervisor points out that the instrument may be revealing for dead patients, but it is definitely not applicable to the living. Bev, on the brink of his endurance, having suffered paranoid seizures and addiction to drugs and medication, performs a test on a patient who has checked into the clinic. As he believes, her reproductive system is mutated, so he decides to take drastic measures and use a retractor during the examination, which ends in the patient’s pain and failure on his part. During a conversation with his brother, he explodes and says: There’s nothing the matter with the instrument! It’s the body! The woman’s body was all wrong![12] This shows a desperate attempt to fix something humane and corporeal with medicine, to show its power and importance, that only medicine can fix damaged ideals, and that femininity is monstrous. The betrayal of which he accuses his partner, orders him to treat all women the same way, through special treatment. He tells himself that each of them is a monster along the model of Claire, he has to bring their normalness back. Beverly creates medical instruments to treat deformed women. With the help of a local sculptor, he makes metal objects to restore women to their biological function of bearing children. They don’t resemble typical medical instruments, but rather sadistic erotic gadgets designed to cause suffering and physical emptiness, and pleasure and satisfaction for Beverly. As Beard says about the instruments, they become the last intense focal point of the film’s exposition of sexuality-as-science, sexuality-as-science-as-sickness, and now sexuality-as-science-as-sickness-as-art.[13] The line between the sanity of medicine and the sick beliefs and convictions of a mentally unstable man is blurred. The tools Beverly made look more like instruments of torture or medieval medical treatments than instruments that can be used in the twentieth century, when medicine is constantly evolving and improving – Cronenberg presents medicine as a discourse of violence. Bread also states that in keeping with the direction of the whole film (and the trend of Cronenberg’s cinema in general), these sadistic weapons are not used upon a woman, they are used upon a mutant self.[14] The instruments are not meant to strip a woman of her identity, but only of an anomalous part of her body, something to get rid of – or just as one should get rid of one’s twin?

Everything that is human and related to reproduction plays a major role in the film. In fact, the film itself begins with a scene where the roughly eight-year-old Mantle brothers are discussing sex both between fish:

– They’re having a kind of sex. The kind you wouldn’t have to touch each other.

– I like that idea.[15]

Then they ask their friend if she would like to conduct a science experiment with them – sex in the bathtub. This short scene, although it may seem minor against the backdrop of the entire film, reveals and justifies many of the phenomena that are then seen on screen. In her article, Oster analyzes this particular scene and comes to some important conclusions. For starters, the way the conversation between the twins proceeds is intriguing. Walking down the sidewalk, they talk about reproduction, which suggests that this was hardly their first conversation on the subject. Oster sums it up as a sort of unrepressed sexual maturity seems to accompany their thoughts at a time when they should be enjoying a childhood free of questioning of libidinal impulses.[16] Their choice of vocabulary, seriousness, and deliberation show a scientist’s mind locked in a child’s body, where they look at sex from the medical and scientific side, rather than the purely physical and emotional side – something more than a child’s mind can comprehend, but also a different perspective than an adult’s on sexuality. Their future work allows them to act as reproducers without performing the physical act – their work is pure, scientific, and ideal.

Another aspect that the author touches on is the motif of water, which appears in this short but concise scene. Oster says that water can be interpreted as the womb and the return to it as a state of perfect happiness.[17] The woman’s womb is filled with the fluid – water – that the brothers shared in their mother’s womb. This water can be further interpreted as the life the twins wish to continue sharing together, and Claire, a disturbing element in the Mantle saga[18], stirs up a storm in their waters and destroys their previously peaceful environment. It is interesting to note that despite the plethora of themes such as motherhood and gynecology, or the womb, which are closely related to womanhood, the role of the Mantles’ mother is absent in the film. It is not known if she was or if she is. One can assume that she was their source of inspiration – to discover the roots of their twinning and find them in treating the women in their clinic. As Beard believes, In so many ways, Claire begins to seem like the missing mother, the one whose absence has condemned Beverly to a condition of incompleteness. Now she is back, now Beverly can (re)unite with her and become whole again.[19] However, Claire was not, is not and will never be a mother. She says of herself that she has psychosexual problems, starts taking drugs to increase sensations, and enjoys sadomasochism. Is this why Beverly’s frustration grew so much? Because he couldn’t cure her like other patients? Was it because she took pleasure in sex, which should be a source of reproduction, not mundane pleasures?

In Dead Ringers we see the decline of the main characters, their gradual, though at times rapid, degradation. In one scene, when Beverly is already an addict, he recalls the story of the Bunker siamese twins.

Chang died of a stroke in the middle of the night. He was always the sickly one, he was always the one who drank too much. [quoting]

When Eng woke up beside him

And found that his brother was dead,

He died of fright

Right there in the bed.[20]

At this point, Beverly plays the role of Chang – devastated by the consequences of his behavior, sick mentally and physically, always the weaker, submissive one – and Elliot, as his guardian, can only die of horror at the loss of his brother.

For most of the film, as I mentioned before, Elliot was the dominant, gallant, and extroverted one, and Beverly followed him in his shadow, obediently following his instructions. In contrast, after their transformation and addiction to drugs, the roles are reversed. The brothers are now indistinguishable – both equally damaged with sorrowful eyes full of emptiness. Now it is Elliot who is Chang, the weaker brother, who dies, and Beverly – Eng, who then passes away out of grief and fright. Beard interprets the transformation of the characters as a transition of masculinity to traits attributed to women – helplessness and misery, who at the same time take great recourse to their masculinity to objectify women as research objects in medicine, specifically gynecology. Brothers’ dread and inability to gain full control over women, their otherness and the monstrosity they so fear, slowly pushes them to do the same. At the end of the film, it is Elliot who becomes the woman – mother. Beverly places Elliot in a gynecological chair, and then using his instruments, made for treating monstrous women, cuts a kind of womb in his brother’s abdomen. The next morning, unaware of anything, he finds his brother in the living room and sees the results of his actions. He cuddles up to Elliot’s corpse in the way he would like to enter the cut womb, the womb of his mother – his caretaker – to feel stability and security again.

Dead Ringers can safely be called a very sad film that depicts the sadness and emptiness of human life. Cronenberg once again looks into the depths of human psychology and pushes the boundaries in contemporary cinematography. He depicts the fragility of human existence and identity as well as raises questions about the nature of existence. He manages to strike a balance between fascination and empathy as well as repulsion. He blurs the boundaries between reality and illusion or psychosis. The drama of masculinity, the terrifying fear of abandonment and loneliness, is played out before our eyes. Masculinity that fears women, their otherness, their monstrosity – the mutant woman. A masculinity that tries to gain control over women to keep them in line and outdated patterns of femininity. A film about men who so desperately need women and a return to their origins – who envy and desire women.

Weronika Kaczmarska

MA English Philology, Vistula University

——-

Bibliography

- Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.

- Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, pp. 234 – 276.

- Rodley, Chris, editor. Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Toronto: Knopf, 1992, p. 149.

- Creed, Barbara. Phallic Panic: Film, Horror and the Primal Uncanny. Melbourne U.P., 2005, pp. 63 – 67.

- Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, pp. 181 – 188.

[1] Rodley, Chris, editor. Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Toronto: Knopf, 1992, p. 149.

[2] ibidem

[3] Creed, Barbara. Phallic Panic: Film, Horror and the Primal Uncanny. Melbourne U.P., 2005, p. 64.

[4] Creed, Barbara. Phallic Panic: Film, Horror and the Primal Uncanny. Melbourne U.P., 2005, p. 45.

[5] Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.

[6] Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, p. 182.

[7] Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 237.

[8] Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, p. 182.

[9] Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 22.

[10] Creed, Barbara. Phallic Panic: Film, Horror and the Primal Uncanny. Melbourne U.P., 2005, p. 65.

[11] Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, p. 188.

[12] Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.

[13] Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 256.

[14] Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 256.

[15] Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.

[16] Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, p. 184.

[17] Oster, Corinne. ‘Dead Ringers’: A Case of Psychosis in Twins. American Imago, vol. 56, no. 2, 1999, p. 185.

[18] Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.

[19] Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 263.

[20] Cronenberg, David, director. Dead Ringers. Astral Films, 1988.